Acts of Disruption for Liberation: Counterstories, Accessibility, and Accomplices

By Nicollette Davis

Before, during and after library conferences there’s often a lot of discussion and excitement about traveling, the sessions, planning outings, and networking opportunities. Some institutions and scholarship programs require staff to write about their experiences at the conferences to prove their attendance. A couple years ago, I spoke with a librarian who had to write such a piece and asked her about her narrative. At the time I was not afforded the opportunity to go to conferences but I was interested in learning about what it was like. She laughed and said something along the lines of, “Oh nobody reads those, who cares?” It’s true that those conference accounts are often fluff pieces, but the stories are important, particularly for those who are not in the room. Conferences give us the opportunity to connect ideas and people. Often, many of the people who make the conference and its experience are unheard or altogether excluded.

As Mondrea (Mondo) Vaden points out in their work, counterstories are important to bridge the gap between the known and unknown narratives, specifically related to disability studies. Counter-storytelling is an act of resistance and pushes against the white, able-bodied, heteronormative ideals that are often hypervisible. Solórzano & Yasso define it “...as a method of telling the stories of those people whose experiences are not often told (i.e., those on the margins of society) .The counterstory is also a tool for exposing, analyzing, and challenging the majoritarian stories of racial privilege. Counterstories can shatter complacency, challenge the dominant discourse on race, and further the struggle for racial reform.” While this definition specifically focuses on race, I believe it can be applied with an intersectional framework. After conferences we are often shown smiling in group pictures, showcasing the “Can’t wait til next year!” and “I had a great time!” sentiments. Usually, we are missing the accounts from those who are often left behind. While it might seem like conferences are overflowing with everybody from everywhere, it is far from the truth. They are expensive, time-consuming, difficult to navigate, and many are excluded based on their job title alone.

In the March 2023 issue of American Libraries Ione Damasco’s “Transforming Culture” piece pulls from facets of Tema Okun’s work related to white supremacy culture and exclusivity. Damasco’s example about inclusivity says, “Your library might host a film screening that is inclusive because the film is centered on the experiences of a specific underserved community, but it may also be exclusive because the film does not have closed captions that allow people with hearing disabilities to enjoy it. The opportunity to be truly inclusive was missed because of an oversimplified idea—that if a film is about diversity, then the event promotes diversity.” One of Okun’s tenets of White Supremacy Culture is the act of progress and “bigger is better,” the idea that only increase shows progress and that stagnancy or cutting back is seen as a failure. Libraries and library workers feed into this by valuing numbers over people, including in their conferences. Post-2021, after all that we had learned, the knowledge we acquired to make things just slightly more accessible seemed to be tossed out of the window in favor of the appearance of progress.

In February 2023, the long awaited Joint Conference of Librarians of Color (JCLC) was held in St. Pete Beach, Florida. Back when the conference location was announced, many library workers wondered about a virtual option. The announcement came in as Covid continued to infect and take the lives of many people globally. Mandatory mask mandates were still in place and emergency rooms were still filled with sick people who didn’t know their fate. With optimism and excitement, the conference planning continued with no virtual option in sight. I had never attended a JCLC conference and unfortunately had never heard of JCLC until I became a member of We Here. We Here is a supportive community for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) library workers, archivists, and LIS students and through the community, I became excited about attending my first JCLC conference. Many of the BIPOC library workers who I admire and have worked with have attended the conference, many of them forming close bonds that not even distance can diminish. I have heard how JCLC feels like a homecoming and the warmth of feeling seen and understood is something that every BIPOC library worker should feel not just once every 4 years, but throughout their work life. I was ready to experience that warmth, the sun and light of people who see me and understand the nuances of being a Black woman in a field that is predominantly white.

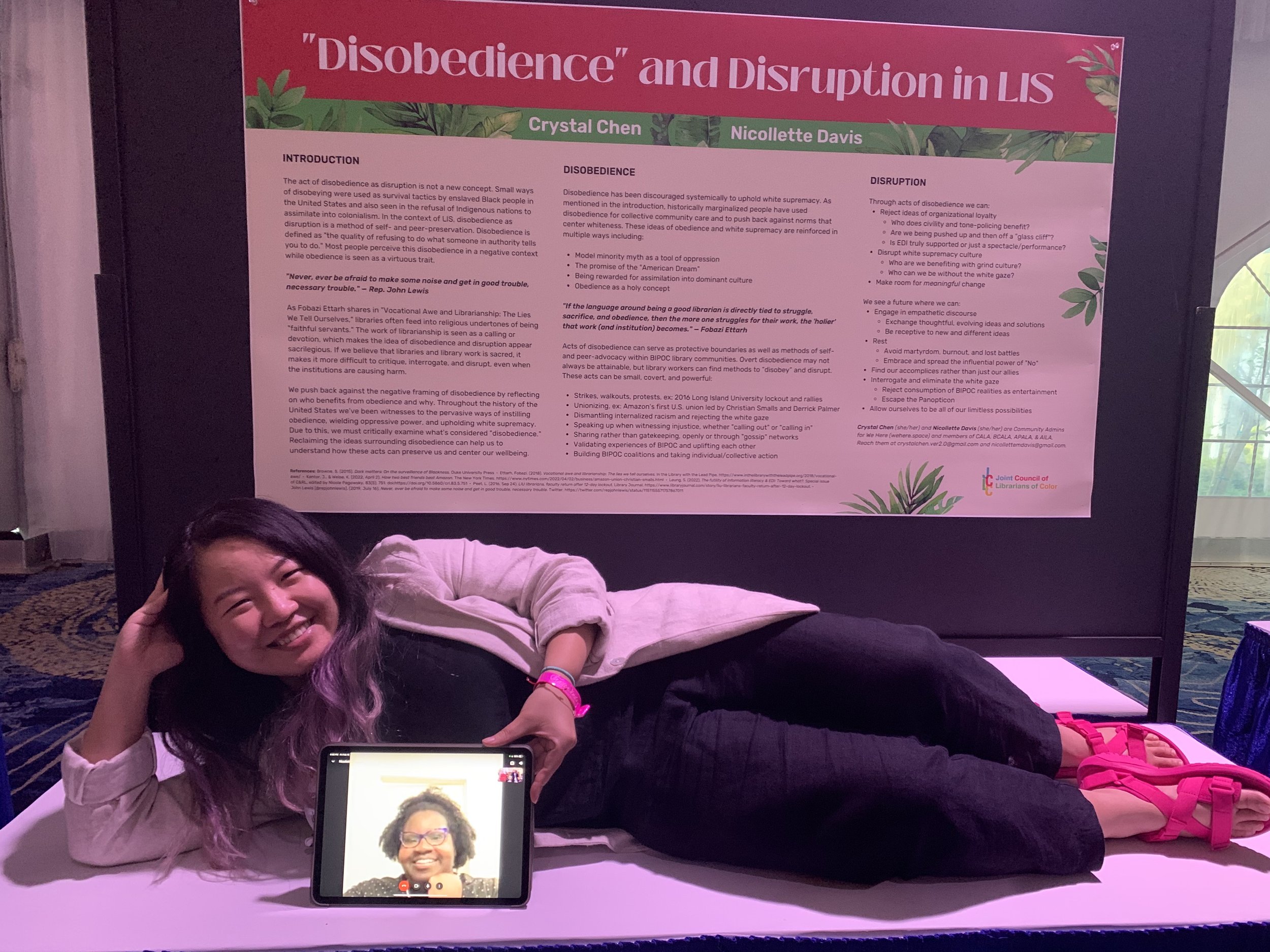

I briefly served on a planning committee and my friend and fellow librarian, Crystal Chen and I pitched a poster proposal which was accepted. For personal reasons, I was unable to attend the conference. Crystal reassured me that things would work out even if she had to bring her iPad and broadcast me on it. At the time, that was said rather jokingly, but who knew that it would actually be the case. There I was at JCLC while being hundreds of miles away in Louisiana. Obviously, I felt guilt for not being there physically to help manage the small crowds forming in front of our poster. There were limitations of my virtualness, but we did the best we could. Some attendees thought that I was a video recording but I was very much live! I spoke to quite a few familiar faces, met some new ones, answered questions and went on a tour of the poster session checking the many wonderful posters (thanks to Crystal who walked me around).

When many people think of accessibility, they think of it in a flat, linear way instead of the dynamics of what it is. Accessibility isn’t just about who can access something with ‘reasonable accommodations’ but also who is missing and why. What does a homecoming look like when part of the picture is missing? How can we show up and bring folks who do not have privileges “home”? Sometimes people rely on organizations to make explicit changes for progress. The onus should not have to fall upon those who are already being silenced, but if history has taught us anything, it has shown us that a movement starts with forming bonds with each other, our community, and it’s our collective care that gets us through and perhaps to the other side. When we see that the organizations aren’t making those changes, how do we prevail and stand up for the things we believe in?

It wasn’t until after reflecting on the conference that I realized how my presence was a small disruption; by pushing against the no virtual option being there virtually. I know I am not the only one. I think about those who have come before me and those who have probably spoken these exact sentiments long before my existence in this field. I mourn for those lost and unheard voices. To them, I credit these words and thoughts. I can only hope for better futures for us all.

In the physical sense, even when the building or place is compliant with the American Disabilities Act (ADA) they are often illogical and skated along by doing the bare minimum. Librarian and Disability advocate J.J. Pionke points this out by sharing, “...if a [person] uses a walker, then building a ramp into the building is the obvious solution. Putting that ramp by the dumpster or in the back of the building doesn’t matter to the medical model because the ramp is there.” As the child of a disabled parent, I realized how inaccessible the world was for my mother.

I particularly remember when I was a freshman in high school, I invited my mom to attend a recital for my piano class. I wasn’t a part of the recital and in fact, I wasn’t doing very well in the course, so my teacher graciously offered me bonus points if I attended the recital. It was being held in the school theater which was easier to navigate from the inside of the building rather than the outside. From the outside, one would have to walk around the large theater to get inside and down a generous hallway. In my youth, I didn’t think it was “far” but when I explained it to my mom, she asked if there was a side door. I told her that there was but that it was locked and no one had ever used it. As a 14-year-old, all I wanted to do was fit in and not draw attention to myself. I forgive myself for my actions as a teenager but acknowledge where I used to be mentally. I went inside along with my brother and took my seat. My brother went to the side door and opened it, allowing my mom access to the theater. Sometimes, you need an accomplice to open the forbidden side door instead of being led by the fear to conform and sulk in guilt after the fact. This is also to say that proximity to someone with a disability does not always equal understanding and accomplices are always better than allies.

Access also doesn’t solely lie in the physical sense but also financially. Conferences are expensive and many library workers lack institutional and personal funding to attend. As I mentioned previously, one of the primary goals of librarianship is to provide information, but sometimes we gatekeep information within our own field by excluding folks who cannot attend due to finances or ability or even things like lack of access to extended childcare. In Tiffany Grant’s article, “Black Lives and COVID-19: Dying to Breathe,” she states, “Institutional oppression establishes systems that are favorable to a preferred group while simultaneously instituting barriers for members of the non-preferred group.” Even when those preferences aren’t explicit, they are often inferred and supported by those who fit the status quo, leaving those who are historically and continuously marginalized out of these spaces.

Prior to JCLC, I attended LibLearnX in New Orleans in January 2023. When you register for the conference, you’re asked if you need accommodations such as a mobility scooter or a quiet space. However, there’s a lack of maps and information about travel, parking, distance, braille signage, etc. These are things that disabled folks have to consider well ahead of time. I heard from some attendees how uncomfortable they felt after having to navigate a new space with little insight. And while all of the spaces were legally ADA compliant, were disabled conference goers well cared for? To ask this question is not to reduce the time and labor of conference organizers who worked on accessibility issues, but it’s to provide space for critical evaluation in order to make necessary changes. It is a question to explore the counterstories and recognize the limitations of allyship. Being an accomplice requires a higher level of vulnerability and accountability. When things get tough and I need more than someone to stand beside me at the wall, but someone to help me wreck the wall to eliminate the barriers that hold us all back from liberation.

Works Cited

Damasco, I. (2023). Transforming Culture: Strategies for combating workplace inequity. American Libraries. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2023/03/01/transforming-culture/

Grant, Tiffany. (2022). "Black Lives and COVID-19: Dying to Breathe." WOC+Lib, www.wocandlib.org/features/2022/5/3/black-lives-and-covid-19.

Okun, T. (2022). Progress is Bigger & More | Quantity Over Quality. White Supremacy Culture. https://www.whitesupremacyculture.info/progress--quantity.html.

Pionke, J. J. (2020). “Library Employee Views of Disability and Accessibility.” Journal of Library Administration, 60(2), 120–45. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2019.1704560.

Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical Race Methodology: Counter-Storytelling as an Analytical Framework for Education Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800103

Vaden, M. (2022). CRT, Information, and Disability: An Intersectional Commentary. Education for Information, 38(4), 339 – 346. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-220055

Nicollette Davis

(she/her) is based in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and is an assistant librarian at Louisiana State University. Before moving into academic librarianship, she spent time working in public libraries in various roles. Her interests include critical librarianship, BIPOC community building and engagement, and person-centered practices in LIS. She was named a 2023 Emerging Leader by the American Library Association.

Instagram: @LiteraryJones