Departures & Arrivals: A Musical Memoir

With gratitude to peer reviewers Alonso Ávila and Anastasia Chiu, infinite thanks to audio producer Sage Tanguay of the University of Virginia’s WTJU, and praise to text editor Jessica Tingling

Text and sound design by Katrina Spencer; for Jerí, Troy, JoAnne, We Here, and Sarad

Table of Contents

Author Katrina Spencer and audio producer Sage Tanguay work with Adobe Audition to create the 25-minute audio recording of “Departures & Arrivals: A Musical Memoir” at the WTJU radio station in Charlottesville.

To contribute to Katrina’s next departure and arrival, visit the Departures & Arrivals Go Fund Me or find her on Venmo at Katleespe or via CashApp at $Katleespe. Find more writing from Katrina with Vinegar Hill Magazine, Charlottesville Tomorrow, Library Journal, Information Today, up//root, and McSweeney’s.

Accompanied by a 50-song, thematic Spotify playlist, this work tracks the emotional and professional journey of an academic librarian across three states from 2016- 2023. Every song is meant to evoke a feeling or a concept from the writer’s life, including hope, isolation, desperation, ceaseless mobility, the pursuit of money, self-actualization, strategy, and resolve. As mentioned in the author’s previous work, “Uprooted, Nomadic, and Displaced: The Unspoken Costs of the Upward Climb,” there are many positions within academia and academic librarianship that require workers to move from one locale to another. For Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, these moves may oblige us to confront more challenges of adjustment than our white peers. Securing community and a sense of rootedness for these same groups can prove to be elusive and impact one’s mental health. For anyone struggling with their mental health or just looking to maintain it, please see the compilation of resources at Innerbody, the Mental Health Coalition, and/or “55 Mental Health Resources for People of Color” from Online MSW Programs. Connect to the Spotify playlist that houses the musical memoir. Tweet @Katleespe with the hashtag #LISmusicmoment to share a song that represents your library and information science (LIS) career or the LIS moment that you’re in. Or find me on the new social media platform Spill with handle Katleespe.

“Mimi,” by Mapumba; translation sourced from Mapumba’s YouTube page

English

I say thank you father

For giving me this path

Oh God father be with me

for this is only the beginning

This guitar is my life

It was given for a reason

That’s why I will sing

Till the end of my life

That’s why I say to you

Follow what your heart[‘s] desires

For the gift that you’re given

Is the source for your happiness

And even God himself will rejoice for you

Lalala lala lalala

Swahili

Mimi na piga asanti sana

Kwakunipa njiya iyi baba

eh we Mungu wangu

Ukuyenami kwakama iyi ni mwanzo eh

Gidari iyi njo maisha yangu

Mungu ashikunipekyo bule

Njo kile ntaimbo mpaka mwishoamiasha iyi yangu eh

Kumbi wewe unisikiye mimi wewe

Fwata kile roho ina panda

Kwanikile mungu alikupa

Kitafania ufurai ufurai ufurai

Na mungu baba naye atapenda

Twimbe

Lalala tala tala talala…

Back in 2016, I woke up one morning not knowing where I was. While disoriented, I wasn’t hungover: I don’t even like the taste of alcohol. And I wasn’t high: the hardest drugs I do are acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and amoxicillin. My body was in Madison, Wisconsin, but the rest of me was not. I didn’t recognize the walls surrounding me or the bed I was in. It took my mind a while to catch up. My heart remained in Dakar where I had just completed a library fellowship and fallen in love with a man who was off limits to me. My community was in Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, where I’d spent the previous three years of my life. And my family was where it always is: California. As I lay awake, I waited for all of me to come together, but not all of my parts had arrived… and wouldn’t. I’ve been divided for a long time. How do you get all of you in one place? The moment reminded me of Putumayo’s African Dreamland compilation in which Mapumba thanks god for the journey and recognizes “this is only the beginning.”

The author (fourth from left) with her family in Los Angeles circa 2008.

I was launching my career as a librarian and the first (and only) job I was offered, after a generous number of interviews, was up in the land of Bucky Badger, a mascot at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. In this chapter of my career, I was eager to prove my worthiness and searching for ways to make a mark. I felt like the protagonist in a slew of 1980s songs: they didn’t “stop believing” (Journey), were “coming out” (Diana Ross), and were headed for “Broadway,” (George Benson) presenting themselves to the world, harboring raw, pulsing talent, and holding a measureless belief in their capacities that were just waiting to be discovered. They were going to “remember my name” (Irene Cara).

I was right. And I was wrong. I’m good at the things I choose to do. But, if I’m honest, I was denying what I wanted to do most. I opted for the “sure” path: one that would allow me to make my student loan payments on time, the one that would offer me three square meals a day and health insurance, the one that would allow me to work and live in climate-controlled environments, in relative ease and comfort. It was a self-protective mechanism informed by the aggressive churn of capitalism. I didn’t want to struggle to make rent or wonder where my next meal was coming from. So I wrapped up my art and put it on a shelf.

In that first phase of librarianship, I couldn’t quite figure out how to plug in, however. Or, I plugged in, but the work I was doing was consistently “library adjacent.” I created social media series, translated comics, and shaped advertisements. Very little of my chosen work went towards information literacy, academic integrity, or collections-- some of the pillars and essential stuff of librarianship. What enthused me were projects that centered on culture and communications. And when an opportunity arose to work on a familiar campus with foreign languages at a pay raise of an additional $14,000 per year, I took it. “Mama didn’t raise no fool,” a popular, African American saying. Having crossed 10,000 miles in a year’s time, as Lenny Kravitz sang, I was “always on the run.”

Generous people, Jerí and Troy, helped me to pack my belongings which hadn’t had enough time in one place to collect any dust. And people like Roberto Delgadillo, rest in peace, donated to my latest departure so I could make it to Vermont. I broke my lease, paid the penalty, and headed northeast. There was maple syrup, green mountains, limited housing, and dark winters that lasted five and a half months.

In my work, I was granted enough autonomy to start an oral histories project, author a book review column, and organize a series of popular trivia events. The consecutive successes were rewarding, for a while, and built my confidence in approaching a broad array of tasks. But after overextending myself, I came to realize that the rurality of my environment left me with little that could replenish my soul. I had to drive an hour to get to a city and three to get to a diverse metropolis. The longer I stayed in Vermont, the more magnified my isolation became and I felt like Khalid when he sang to a lover, “Send me your location.” I had and have a desperate need to connect…

I was hungry for community that Vermont couldn’t provide. My students were wonderful, but we weren’t at the same stage of life. My weeks were no longer ruled by graded assignments. I didn’t vacate the premises during summers as they did. And the conversations I was having with colleagues surrounded where to invest for retirement, not where to intern prior to entering the job market. I could contribute to the campus culture and innovate… but if I wanted to sit in a lounge that played R&B, soul, or funk with other people who looked like me… I’d have to travel 137 miles to Montreal or 268 to New York City. I didn’t want to displace myself every time I wanted to live. Thank God… it was around this time that We Here, a community space for library and information science workers of color, entered my life. This group and its members offered me a virtual community while the geographical one struggled to manifest.

Members of We Here applauded my labor when I did well. They commiserated when I intimated pain and disappointments. They laughed when I shared jokes. And they shared their successes, quandaries, and struggles. They became a refuge. If I were to apply a 21st century metaphor to We Here, I’d say “they never leave me on read.” And when you live in places where you feel unseen or unheard, responsiveness is key. For many Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, you can be surrounded by people, but “they don’t really know you” (Libianca).

I stayed in Vermont for just over three years and I found myself with some symptoms of depression and engaging in some self-destructive behaviors. I became irritable. I stopped innovating. I dated people simply because they were nearby. And I applied for work in Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and more. Two of these didn’t find me to be their preferred candidate. Another two of these searches resulted in offers, but they, in turn, weren’t competitive or compelling enough to uproot my life anew. For awhile, I felt as though I had “nowhere to run” (Martha Reeves & the Vandellas). I saw a therapist and she told me “It sounds like you feel stuck.”

A colleague told me he took medication to help maintain his mental health. I resisted the pursuit of medication-- wrong, right, or misled-- convinced that the depression was situational. If I could change my situation, I thought, what would I need medication for? I wanted something bigger, Black colleagues, something new, and more diverse. As Disney’s Belle put it, I wanted much more than the “provincial life” (Richard White, Paige O’Hara). Then I applied to Virginia, and, finally, it was a mutual match.

When you live in a rural town of 8,000 people, one of 50,000 represents growth, expansion, and possibility. Could I have Black colleagues?! Pizza delivery?! Someone to date?! My asks for 2020 were few. I signed the papers, and somehow an airborne virus managed to ruin even that. I drove 598 miles south and started a new role nonetheless. The town was bigger. There were more Black people on the professional roster. “Dating,” ultimately, wasn’t quite what Tinder, Hinge, or Bumble were offering, but I settled in.

The coronavirus didn’t allow us to do much. After sitting on my couch watching YouTube and Netflix several weekends in a row, I needed a way to get out, to explore, to discover, to experience. And that’s when I started driving for Uber. I never had before, but I’d purchased several items of furniture on a credit card and wanted to eliminate the debt. And in the absence of community events and weekend activities, it was a viable option for getting out and interacting with people. It introduced me to the layout of the land and made home feel like less of a prison.

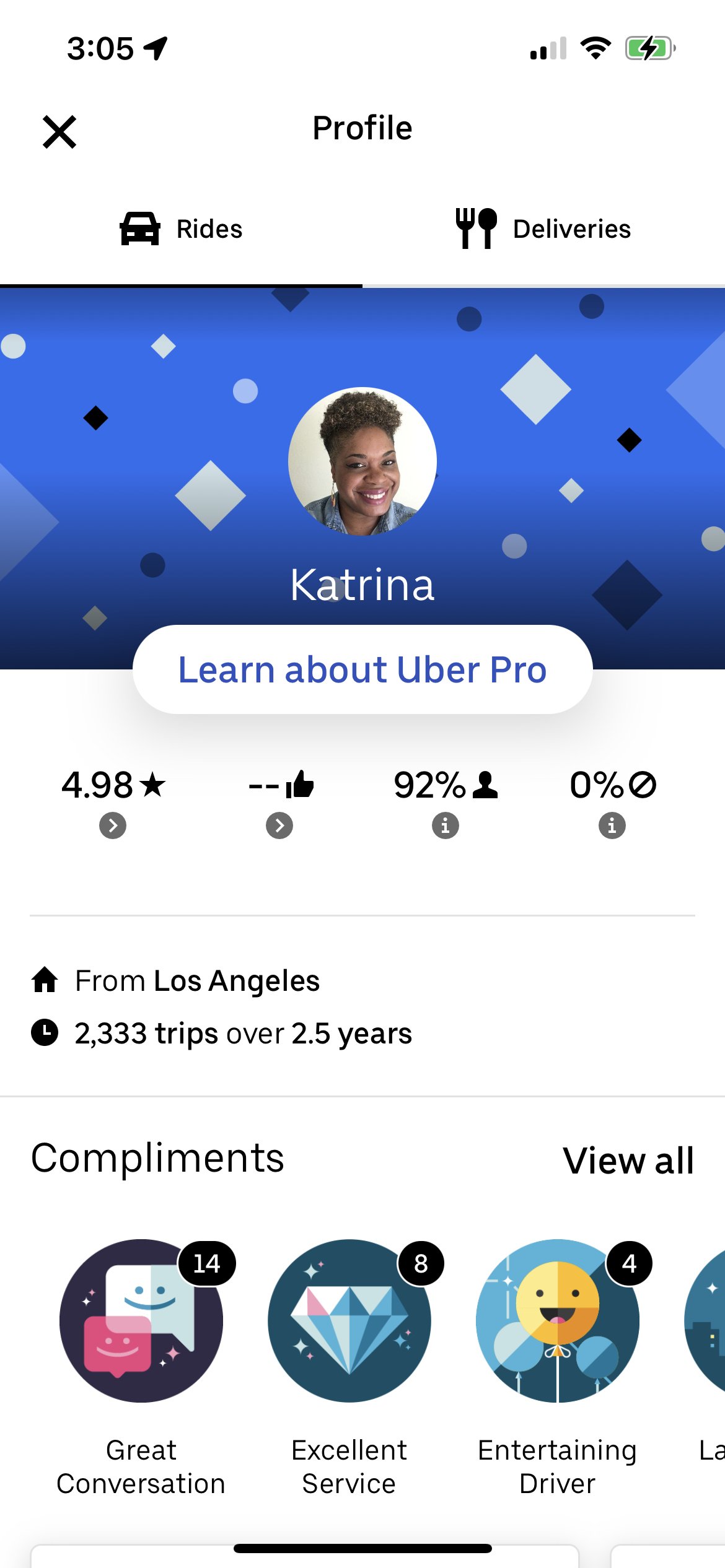

The author’s driver profile from Uber indicating her 4.98 rating out of five and a 92% acceptance rate of rides. She has provided 2,333 trips in 2.5 years.

The incentives and demand were just right. On average, I was earning as much as I did as a librarian, if not more. When the students were in town Friday and Saturday nights, I could expect pay of $37.50 an hour. If there was a football game, my rate could reach $52 an hour. And, as I’d learn, “money can drive some people out of their mind” (The O’Jays). Between my full-time and part-time work, I was banking six paychecks a month, which was welcome because my rent had gone from $825 per month in Vermont to $1,429 in Virginia. Working only one job, I had just enough to pay it and nothing left over in discretionary income. In my new locale I could either live in a very nice place and be unable to afford leisure or choose a place that was a bit run down and eventually conjure up getaways that might be worthwhile. I chose the latter… yet something remained familiar: perpetually leaving “home” to experience life.

For the first time in my life, I had enough money to make long-term investments. Then the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) informed me that I owed them money. So I drove to pay that debt. Then my car needed repairs. So I drove to pay that debt. I was the woman Donna Summers was singing about: “She works hard for the money, so you better treat her right.” I was driving, masked, evenings and weekends, Wednesday to Sunday, up to 20 hours a week, coming home exhausted, and receiving deposits every Tuesday morning. “Hand over fist,” I was “bringing home the bacon,” as they say, and buying whatever the hell I wanted. I’d never had the chance to be frivolous before. And now I was purchasing amarena cherries from Italy, barf bags for the car, and more nail polish than I could ever use. And when my family needed financial support, I could step in without losing my own financial balance. It was like one of those progressive, time lapse scenes in a gangster or casino movie where you can’t stop the flow of cash, the pick ups, the drop offs. It was a well oiled machine. But how long could it last? Every machine, eventually, catches on a kink. Imagine if I could work just one job and accomplish all of the above. Is it so unfathomable? Well is it? I was “driving Cadillacs in [my] dreams” (Lorde.)

It turns out the new found riches came with a cost. My weekends were gone and not my own. I sat sedentary in a car for 6-hour stretches, which can’t be good for the body. I was often eating fast food from quick places I could find on the road. I was working so much that I forgot who I was. Something unexpected would happen where I couldn’t drive or there was little demand and I thought, “Now that you have some free time, what would you like to do?” And I, stunned by the unexpected stillness, tonically immobilized, couldn’t answer the question. “What are your hobbies?” I couldn’t remember. “What do you want to explore?” I drew a blank. In my gaze, like in a Warner Brothers’ cartoon or Rihanna’s words from “Pour It Up,” “All I see is signs, all I see is dollar signs/ Money on my mind, money, money on my mind.” I was no longer human; I was an automaton. A walking wallet. The debts were paid, but I lost something: myself.

The librarianship? Oh, yeah. That was… okay. I was working from home and the people I was hired to serve seemed preoccupied with the transition from in-person classes to online and keeping themselves, their families, and their students safe. Warmly welcoming a new employee in a new role was lower on the list of priorities. I cannot fault them.

I started thinking critically about the nature of work. Then I started writing critically about the nature of work. I spent all of 2021 drafting a piece on overcommitment, uncertain it would ever see the light of day. I did some instruction. I did lots of promotions of our collections. I learned about challenges in the pursuit of African American genealogy. I served on a search committee. But I still felt distant and pensive with regard to my new role. Moreover, the pandemic kept me from my family for three years, the longest period I hadn’t seen them in my life. And part of me began romanticizing home. I kept my eye on job postings that were further out West where my humans were and are. I applied, unsuccessfully, to a few. And I was “stuck” again. My parents were aging. My city was changing. And there was nothing I could do. I wasn’t forming new relationships in my new locale and couldn’t access the ones I held from Day One. I’m not so certain California is the answer to my troubles. Nostalgia will have you believe “it never rains in Southern California,” (Tony! Toni! Toné!) but this year saw floods. The home you leave isn’t the one you return to.

The author poses for a photo in Paris, France at the foot of the Sacré-Coeur.

At this point, I wasn’t driving for Uber to escape the walls of my home or to escape debt. I made a new goal of making sure my earnings would create desirable experiences for me. Paris. D.C. Virginia Beach. Richmond. São Paulo. Salvador. My Uber earnings took me to all of them. But there was one consistent theme: I went to each of them alone and in an effort to access the life I didn’t feel I was living. Hiking up to the Sacré-Coeur in Paris, avoiding the pickpockets, I posed alone. Sitting outside of the Igreja de Nosso Senhor do Bonfim, selfies again were on the menu. I wasn’t feeling so “tall and tan and young and lovely” (Astrud Gilberto, João Gilberto, Stan Getz, et al). I was feeling more alone, understimulated, bamboozled, and at a loss for answers. It wasn’t Eat, Pray, Love. It was more What-series-of-choices-have-brought-you-to-this? and Is-it-giving-what-it’s-supposed-to-gave? Is-the-math-mathing?

The author takes a selfie in Salvador, Brazil outside of Igreja de Nosso Senhor do Bonfim.

In the meanwhile, back on North American shores, I busied myself by responding to reference requests, carrying out paired teaching, developing recorded tutorials for Ancestry, serving on a campus-wide committee that disbursed funds for diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility efforts, being part of the editorial board for the Journal of Library Outreach and Engagement, studying foreign languages that would help me to further my subject expertise, and shaping thematic, virtual webinars. But relationships? There weren’t many. My resume became bloated to the point that I was sick of looking at it. A free weekend night would roll around and I realized I had no one I could ask out for coffee. Something was off and likely had been for a while.

I had been documenting my “successes” for my annual reviews, but little of what I was “accomplishing” touched my soul. I was effective, but not impassioned. And the ongoing pandemic gave me a greater period for reflection than ever before. On a new quest, I gave myself a challenge of carrying out ten paid writing gigs in the year 2022. I’d been writing for free for years and I was pivoting to see if I could earn money for my writing. It didn’t matter if the pay was $20, $200, or $2,000. The gigs just had to be paid and published. I was then working three jobs: librarianship, Uber, and freelance writing. The first paid writing gig was “Overcommitment” via We Here’s up//root. Another was “Uprooted, Nomadic, & Displaced: The Unspoken Costs of the Upward Climb” with Information Today. The last was “Representing the Real World: Diversity in Publishing Imprints” for Library Journal. Several would be for Vinegar Hill Magazine, a publication I would later come to edit. By the time I got around to writing job number eight, I realized there was something shy but insistent that I was nurturing inside of me, whether I was trying to or not. Librarianship gave me the safety and predictability that perhaps anyone coming from a low-income household and having $163,000 worth of student loans needs… but writing was what would “satisfy my soul” (Bob Marley & the Wailers). Writing gave me focus and I felt antsy if I wasn’t doing it.

A meme of comedian Eddie Murphy floating on water stating “Y’all be afraid to start over, this like my 4th life”.

It was around October 2022 when I seriously asked myself, “What if I were to pursue a degree in journalism?” It was an “intrusive” and disruptive thought that I tried to ignore, but it kept, polite and persistent as ever, coming back. It had been for about six months. As Afrobeat singer CKay put it in “Emiliana,” it was “messin’ with my medulla.” I already had four college degrees under my belt at the time and all the student loans I could ever want. I was six and half years into a steady career in which I was receiving some degree of recognition. “You want a 5th degree?” I asked myself. “To do exactly what it is you’re doing now? Publishing for pay?” The thought didn’t go away, and as someone excessively familiar with higher education’s applications and admissions cycles, given it was late fall, if I were to apply, it would need to be then.

I Googled the rankings for the best graduate programs in the United States for journalism. With only a handful of “high profile” pieces under my belt to offer as writing samples, no room for additional academic debt, and more accrued exposure to the northern cold than any Southern Californian wants, I ruled out some schools that were less likely to offer financial assistance and found in colder climates. Warm weather meant south and financial assistance, maybe, meant public. I reached for something that seemed attainable. The University of Texas at Austin answered my proverbial call. While the foreign languages and area studies fellowship (FLAS) I applied for didn’t work out this time, the Jonathan Tjarks Graduate Fellowship did. It was then that I started making plans to “motor west” (Nat King Cole).

The first page of the author’s transcript showing coursework starting in 2002 at Pepperdine University. The highlighted portions show the author enrolled as a journalism major, that she signed up for a “COMMUNICATION THEORY” course in her first semester, withdrew, and updated her major to creative writing the following semester.

[An aside: Would you believe me if I told you that in 2002 as a first-year undergraduate, I enrolled as a journalism major? And that the prerequisite for courses, Communication Theory, was taught at 8:00 a.m., in a new, flashy building, atop a hill by a white man who assigned the driest of readings? I. could. not. do. it. Though I tried. I withdrew and it has taken me 20 years to “course correct.”]

So I’m here now, two months away from a new adventure, a new departure, and a new arrival. Many people have been asking me how I feel. I feel fine. I’m apprehensive about a few things. My car payment is $400 a month, which is not usually an expense a student’s income can support. I want to find an apartment in Austin that will allow me a public transit commute of under 20 minutes, which may prove harrowing to find. And I’ve wanted to bike for so long but don’t feel it's safe in many North American cities. These are the concerns at the front of my mind. I’m looking for on campus work that will allow me to afford my own life. As the Wu-Tang Clan rapped, “cash rules everything around me.” If anyone would like to contribute to the effort, here’s how with Go Fund Me.

And here’s why in terms of estimated costs soon to come:

Moving expenses: $2,000

Security deposit for lodging: $1,000

Lodging on the road: $650

Gas for 1,400-mile drive: $420

Food on the road: $300

Miscellaneous: $500

With moderate approximations, that’s about $5,000. Other items on my mind? I’ve been working from home for three years productively and mostly contentedly. The idea of leaving home five days a week to interact with others will likely pose an adjustment. However, it will also likely aid my waistline.

I’m not resentful towards librarianship. Like Fat Freddy’s Drop sang in “This Room,” “I wanna love/ I don’t wanna fight.” As a matter of fact, if there’s a way for me to write and continue contributing to the field, I’m open to the idea. For now, I must place one thing down so I can pick up another. Do I think journalism is going to “automagically” (for you, Chris) provide me the community and stillness that I have elsewhere found so thin? No. It may, in fact, exacerbate these scarcities. But fear is not something I allow to rule me, and when there’s a chance for novelty, I choose it.

“I don’t want to be underpaid, forever on the move, feel culturally isolated, be financially obligated to overwork myself to the point that I forget who I am, and log projects that are less than satisfying. ”

I don’t want to be underpaid, forever on the move, feel culturally isolated, be financially obligated to overwork myself to the point that I forget who I am, and log projects that are less than satisfying. These are the issues I want the field to consider as I head out. What is a fair annual salary for a person with an advanced degree? What hardships must be endured for professional advancement, particularly for underrepresented groups? How affordable is the locale where your search committee is hiring in comparison to the wage being offered? How can employees, in addition to getting the job done, experience satisfaction and fulfillment? To the decision makers, I hope there is something here that germinates new ideas within you.

And to the many people who I have met and who have supported me along the way, you know how to reach out to me. “Reach out, I’ll be there” (The Four Tops). I don’t intend to disappear. Librarianship has been the main source of my livelihood for seven years and I expect I still have much to offer. Thank you to those who have taken the time to get to know me and to all who have been my family when my biological set could not be near.

To the green-- those of you enrolled in your iSchools across the country-- enter this field knowing some of the potential trials you may encounter so you can best prepare yourself in advance. You are the stewards of your mental health and must take it seriously, even if the systems around you cannot reliably do so. As for me, I expect to wake up one morning this August in Texas en route to a new orientation. Something tells me it won’t be my last.